Estimating Worst Case SWRs For Modern Portfolios

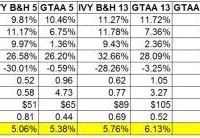

One of the challenges in dealing with modern portfolios like the Permanent Portfolio, the various IVY portfolios, Risk Parity portfolios, etc is the lack of long term historical data. Most of the modern portfolio data for a broad range of asset classes only goes back to 1973. The period from 1973 onward obviously only represents a subset of historical economic and financial conditions. This represents quite a challenge when looking forward and trying to model probable future outcomes for different portfolios. In the context of retirement this fact makes determining SWRs for modern portfolios difficult. The worst case historical 30 year retirement period that determines the SWR for the 60/40 US stock US bond portfolio began in 1966 . Fortunately, 1966 is not that far from 1973 which gave me an idea for estimating SWRs for modern portfolios as if they existed from 1966. Just use the 60/40 return data to for the modern portfolios from 1966 to 1972, then the modern portfolio return data going forward to estimate an SWR for these portfolios. This should give a conservative estimate for historical SWRs form these portfolios which is an apples to apples comparison to the SWR from the classic 60/40 portfolio, aka the famous 4% rule. Let’s see where this process takes us. In previous posts I had presented a variety of statistics for modern portfolios; returns, standard deviations, and SWRs. I also pointed out that the SWRs from these calculations had to be taken with a huge grain of salt. The retirement periods from 1973 onward, when the data for the modern portfolios begins, do not encompass the worst case period in history to retire, the 30 year period starting in 1966. The SWRs for periods starting in 1973 would be significantly higher than for those starting in 1966. In order to get an estimate of what SWRs for modern portfolios would have been going back to 1966 I simply took the historical return series for each of the modern portfolios and used the return data from the 60/40 portfolio from 1966 to 1972 for each portfolio. This will yield a conservative estimate of the modern portfolio SWRs going back to 1996. The assumption here of course is that the modern portfolios would have performed better than the 60/40 portfolios from 1966 to 1972. I think that’s a pretty safe assumption. Below is a table of the results along with the other portfolios stats that I updated through 2014. I did not do this exercise for all the portfolios I track just the ones I discuss the most often on the blog. First, all the portfolio stats in the table are for the period from 1973 to 2014, the actual performance of the portfolios. It is only for estimating the SWRs that I inserted the 1966 to 1972 60/40 return data. I labeled that line 1966 SWRs to make that distinction. As the 1966 SWR line shows, even with the initial 7 year (1966 to 1972) equal performance to the 6o/40 portfolio all of modern portfolios have significantly higher SWRs than the classic 60/40 or even 70/30 US stock US bond buy and hold portfolio. The more broadly diversified buy and hold portfolios, IVY B&H 5, IBY B&H 13, and the Permanent Portfolios have estimated 1966 SWRs ranging from 5.06% to 5.76%. The portfolios that add simple downside risk management (via the 10 month SMA) – the GTAA5 and GTAA 13 portfolios have 1966 SWRs of 5.36% and 6.13% respectively. GTAA 13 also adds value and momentum factors to the mix. Then the portfolios that have diversification, downside risk management, value and dual momentum factors have the highest 1966 SWRs of all. The Antonacci dual momentum portfolios, GEM and GBM, have 1966 SWRs of 5.71% and 5.68%. The aggressive IVY momentum portfolios, AGG6 and AGG3 lead the bunch with SWRs of 7.95% and 8.63% respectively. Pretty impressive all the way around even after handicapping the modern portfolios with 60/40 returns from 1966 to 1972. In summary, modern portfolios have significantly higher SWRs than the classic 4% SWR rule suggests. Even in the forecasted poor return scenarios that I’ve discussed before these portfolios will most likely perform much better than the classic portfolio that the original 4% SWR was based on. Does that mean that these estimated historical SWRs can be used for investors starting to withdraw from portfolios today? Possibly but I wouldn’t go so far as that. As the infamous disclaimer goes, past returns are no guarantee of the future. All we can do is put the odds in our favor. Being the conservative sort, I base my investment allocations on one or more of these modern portfolios but still stick the 4% SWR rule. Then I adjust SWRs accordingly maybe every 3-5 years. Regardless, the superior nature of the modern portfolios, not just in terms of SWRs, should be considered by all investors. Note: There is a lot of information about modern portfolios to glean from all of the portfolio stats in the above table for investors withdrawing from portfolios and even of investors still in the wealth building phase. Just look at the differences in returns/risk and long term wealth for these modern portfolios vs the most often recommended 60/40 buy and hold portfolio. The fact that the 60/40 portfolio is still the most common allocation for US investors is kind of crazy when you see these results.