Backtesting With Synthetic And Resampled Market Histories

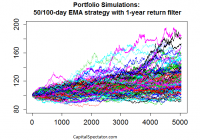

We’re all backtesters in some degree, but not all backtested strategies are created equal. One of the more common (and dangerous) mistakes is 1) backtesting a strategy based on the historical record; 2) documenting an encouraging performance record; and 3) assuming that you’re done. Rigorous testing, however, requires more. Why? Because relying on one sample-even if it’s a real-world record-doesn’t usually pass the smell test. What’s the problem? Your upbeat test results could be a random outcome. The future’s uncertain no matter how rigorous your research, but a Monte Carlo simulation is well suited for developing a higher level of confidence that a given strategy’s record isn’t a spurious byproduct of chance. This is a critical issue for short-term traders, of course, but it’s also relevant for portfolios with medium- and even long-term horizons. The increased focus on risk management in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis has convinced a broader segment of investors and financial advisors to embrace a variety of tactical overlays. In turn, it’s important to look beyond a single path in history. Research such as Meb Faber’s influential paper “A Quantitative Approach to Tactical Asset Allocation” and scores of like-minded studies have convinced former buy-and-holders to add relatively nimble risk-management overlays to the toolkit of portfolio management. The results may or may not be satisfactory, depending on any number of details. But to the extent that you’re looking to history for guidance, as you should, it’s essential to look beyond a single run of data in the art/science of deciding if a strategy is the genuine article. The problem, of course, is that the real-world history of markets and investment funds is limited-particularly with ETFs, most of which arrived within the past ten to 15 years. We can’t change this obstacle, but we can soften its capacity for misleading us by running alternative scenarios via Monte Carlo simulations. The results may or may not change your view of a particular strategy. But if the stakes are high, which is usually the case with portfolio management, why wouldn’t you go the extra mile? The major hazard of ignoring this facet of analysis leaves you vulnerable. At the very least, it’s valuable to have additional support for thinking that a given technique is the real deal. But sometimes, Monte Carlo simulations can avert a crisis by steering you away from a strategy that appears productive but in fact is anything but. As one simple example, imagine that you’re reviewing the merits of a 50-day/100-day moving average crossover strategy with a one-year rolling-return filter. This is a fairly basic set-up for monitoring risk and/or exploiting the momentum effect, and it’s shown encouraging results in some instances-applying it to the ten major US equity sectors, for instance. Let’s say that you’ve analyzed the strategy’s history via the SPDR sector ETFs and you like what you see. But here’s the problem: the ETFs have a relatively short history overall… not much more than 10 years’ worth of data. You could look to the underlying indexes for a longer run of history, but here too you’ll run up against a standard hitch: the results reflect a single run of history. Monte Carlo simulations offer a partial solution. Two applications I like to use: 1) resampling the existing history by way or reordering the sequence of returns; and 2) creating synthetic data sets with specific return and risk characteristics that approximate the real-world funds that will be used in the strategy. In both cases, I take the alternative risk/return histories and run the numbers through the Monte Carlo grinder. Using R to generate the analysis offers the opportunity to re-run tens of thousands of alternative histories. This is a powerful methodology for stress-testing a strategy. Granted, there are no guarantees, but deploying a Monte Carlo-based analysis in this way offers a deeper look at a strategy’s possible outcomes. It’s the equivalent of exploring how the strategy might have performed over hundreds of years during a spectrum of market conditions. As a quick example, let’s consider how a 10-asset portfolio stacks up in 100 runs based on normally distributed returns over a simulated 20-year period of daily results. If this was a true test, I’d generate tens of thousands of runs, but for now let’s keep it simple so that we have some pretty eye candy to look at to illustrate the concept. The chart below reflects 100 random results for a strategy over 5040 days (20 years) based on the following rules: go long when the 50-day exponential moving average (NYSEMKT: EMA ) is above the 100-day EMA and the trailing one-year return is positive. If either one of those conditions doesn’t apply, the position is neutral, in which case the previous buy or sell signal applies. If both conditions are negative (i.e., 50-day EMA below 100 day and one-year return is negative), then the position is sold and the assets are placed in cash, with zero return until a new buy signal is triggered. Note that each line reflects applying these rules to a 10-asset strategy and so we’re looking at one hundred different aggregated portfolio outcomes (all with starting values of 100). The initial results look encouraging, in part because the median return is moderately positive (+22%) over the sample period and the interquartile performance ranges from roughly +10% to +39%. The worst performance is a loss of a bit more than 7%. The question, of course, is how this compares with a relevant benchmark? Also, we could (and probably should) run the simulations with various non-normal distributions to consider how fat-tail risk influences the results. In fact, the testing outlined above is only the first step if this was a true analytical project. The larger point is that it’s practical and prudent to look beyond the historical record for testing strategies. The case for doing so is strong for both short-term trading tactics and longer-term investment strategies. Indeed, the ability to review the statistical equivalent of hundreds of years of market outcomes, as opposed to a decade or two, is a powerful tool. The one-sample run of history is an obvious starting point, but there’s no reason why it should have the last word.