Cash Is King: Was It Ever True?

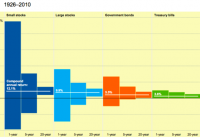

The phrase “Cash is king,” has become a rather ubiquitous part of financial vernacular. I did some research on who first coined the phrase, and while not particularly clear, one source credits the former CEO of Volvo as first uttering the line in 1988. In any case, “cash is king” describes the general power of the asset , its stability, and means to many ends as a financial tool. Despite its weakness as a productive investment today in an era of low interest rates, cash is still a storehouse of value in a global market where equities, bonds , and real estate seem to dominate most portfolios. However, for those that have sold out of or avoided securities markets for the past several years, holding majority positions in cash has presented severe opportunity cost. Sitting on cash instead of holding stocks, bonds , or other assets has not necessarily been the best of timing decisions. Of course sometimes it takes several years for a timing call to play out. Who’s to say that in another five years stocks will be 35% lower, bond yields will be significantly higher, and the only smart play, in hindsight, would have been to hold cash. But, if you are indeed holding a preponderance of cash today, the thought of whether the train will ever return to the station could quite possibly be haunting you at the moment. The longer the bull runs, the more painful and disconcerting it may be to hold true to a cash-heavy thesis and wait patiently for stocks, bonds, or both to become cheap in one’s eyes. Further, with yields inferior to normal annual inflationary pressures in the 1-3% range, idle cash is also losing purchasing power. That may or may not be a tolerable situation for the average investor to endure. So I would argue that the allure of cash as a regal asset has certainly lost some of its sparkle given the recent annals of market history and this era of ZIRP. The incrementally weaker cash seems to be from an investment perspective, the higher the valuation that is placed on other assets. The irony of the matter is that the American dollar, on a global level, has become much stronger over the past year while cash, in and of itself, continues to languish as a coveted asset. The decision of how much cash to hold in today’s market may be one of the most troubling questions for investors. While the sanest thing to do may be to hold a lot of it, given seemingly excessive valuations in equities and minimal productivity out of bonds, how much opportunity cost can be withstood? Buying a stock with a 3-5% yield and stressed valuation may be the “lesser of two evils,” if holding unproductive cash and generating no income is less desirable. While it may seem like the wise decision now, can you live with a 25-50% implosion of capital when and if the market markedly corrects? If, on the flip side, you continue to opt for sitting on cash, how much “pain” can be endured if stocks head higher and bond yields stay low? At some point, admitting an error in a timing strategy or edging back into securities may prove the more prudent move. Another potential outcome is that stocks remain in a trading range for a significant amount of time without a double-digit percent correction. Again, if you are keeping close tabs on valuations, at what point is it deemed “safe” to get back into stocks. While cash still has many attractive properties, low interest rates and demand for other higher yielding securities has diminished a lot of the glitter oftentimes ascribed to it. A higher interest rate environment may prompt a “re-coronation,” but don’t expect that to happen overnight. In the meantime, holding on to substantial amounts of cash may continue to be a frustrating prospect where king may play second fiddle to court jester as an appropriate characterization of its recent value to investors. Original post