Rising Rates Are Good For PHK, Part II

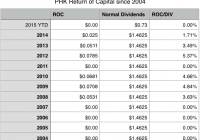

Summary PHK pays out 19.2% of its NAV in dividends to shareholders. This distribution is unsustainable, as the fund’s managers have increasingly relied on active investment in bonds, currencies, and derivatives to sustain payouts with minimal return of capital, thus increasing risk. If interest rates rise, PHK is likely to become less reliant on this riskier approach as its NII will increase. The greatest concern regarding Pimco High Income Fund (NYSE: PHK ) is its payout to NAV ratio. With NAV of $7.62 as of July 2nd and annual dividend payouts of $1.46256, the fund needs to get a 19.2% return to sustain its dividend. Bears argue that this is impossible, and that the fund has to return capital and deplete its NAV to maintain the unsustainable dividend. However, according to CEF Connect , PHK has not paid a Return of Capital in over a year. On top of that, PHK’s history of funding distributions through ROC is moderate. While 1.71% of distributions came from ROC last year, that is down from the prior two years: Also significant: the fund has not resorted to ROC to fund distributions in years of rising rates — years of ROC distributions coincide with times of heightened economic crisis (2008, 2009, 2010) for the most part, although the reliance of ROC during 2012, 2013, and 2014 indicates the fund has had some difficulty in covering distributions from income along. However, the consistent decline in ROC and the absence of ROC so far for 2015 suggests that the fund has been able to wean itself off this stop-gap. There is still a fear that the fund will need to resort to ROC soon, since the average coupon of the fund, according to its most recent holdings report , is 5.165%. Even with leverage, which has fallen to 29% in recent months, it seems there is no way the fund can return 19%. So how can PHK continue to cover dividends when it is paying out 19% on NAV? Clipping Coupons To understand this, we first need to take a step back and remind ourselves that the income a bond holder receives is not necessarily the same as the coupon rate. Bonds are frequently bought at a discount, particularly by institutional investors who have greater access to a market that is much less liquid than equities. Since PHK does not reveal the price it has paid for its holdings, and we can only infer how long it keeps certain holdings in its portfolio, coupon rates are useless in determining the sustainability of the dividend or the fund’s ability to earn a 19% return on NAV. Additionally, the fund’s use of derivatives, its arbitrage and hedging from shorting, and its currency trades make it impossible to know exactly how well operations can fund distributions to shareholders. A better way to understand the return it is getting from its portfolio is to compare its net investment income to its NAV. If we look at these, we see that the fund is now earning about a 12.4% return: This is nowhere near the 19% return that is necessary to sustain the dividend in perpetuity, but is much better than the coupon rates suggest. However, this might become the wrong way to look at this fund if rates rise sufficiently. A Better Investment on Rising Rates While it is undeniable that the low interest rate environment hurts PHK’s NII and its ability to sustain its dividend, the sustainability of those payouts improves considerably in times of higher rates, as the above chart suggests. NII has fallen 43% from 2006 to 2015 due to lower interest rates, and its NII is likely to rise if rates rise and the fund is able to purchase discounted issues with a higher coupon rate. The fund’s recent decline in leverage might indicate its managers are anticipating a rise in rates and are positioning themselves accordingly by freeing up access to capital. Much more crucially: a rise in rates will also help the fund cover dividends, as its NII-to-Dividend Ratio remained well over 100% until the Global Financial Crisis in 2008: Surprisingly, the fund’s NII-to-Dividend ratio remained strong in 2009, when its NAV plummeted to less than $3 at its lowest point. At that time, and for several years since then, the fund has been able to more than cover dividends through investment operations — the kind of arbitrage, churn, and derivative trading that investors pay for. (The significant exception, in 2012, was during Bill Gross’s tenure as manager of the fund. He is no longer with the fund or PIMCO.) The fact that the fund has relied on this kind of active speculation more than before 2008 suggests that there is considerably greater risk in the fund than there was then, but it may also suggest that the fund will become less reliant on such tactics when rates rise. While it is true that the total capital PHK has to invest is much less than in 2005-2008, making it a riskier investment than it was then, its access to higher-yielding bond opportunities in a rising rate environment may make it a less risky investment than it has been since 2008 and throughout the 7 years that the fund maintained its monthly dividend payouts. Conclusion PHK is not without its risks. Its reliance on derivatives and investment operations, particularly since 2009, means greater volatility in dividend coverage and a greater risk in a decline in NAV, as we have seen in four of the last 8 years since the Global Financial Crisis, including this year. At the same time, the fund’s ability to earn higher rates of income in periods of rising rates means that a sell-off due to rising rates is unwarranted. Most significantly, if rates do rise later this year or next year, PHK may find it easier to earn income from the high yield market and become less reliant on derivatives and active trading to boost returns. Disclosure: I am/we are long PHK. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.