Problems With ‘The Long Term’

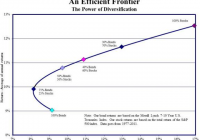

John Maynard Keynes once famously said “In the long run we are all dead.” But the full quote doesn’t often get hashed out. Keynes said: But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task, if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us, that when the storm is long past, the ocean is flat again.” Keynes was pointing out that many economists use a multi-temporal approach to economics to prove very generalized points. Milton Friedman was notorious for this. He was a master of holding multiple positions at the same time thereby allowing him to change the time frame however he pleased so that his argument always worked. For instance, he might say “Oh, velocity of money isn’t having an impact in the short term, but my extensive historical data shows that in the long term, an increase in the money supply will cause velocity of money and inflation to increase” (not a real quote, just to be clear). Many people have heard some version of this in the past 5 years as we waited for the big inflation from QE to come. The use of “the long term” in economics is often another version of “My model has been wrong so far, but if we wait long enough it will be proven right!” This sort of flip flopping could allow someone to hold two opposing positions at the same time and get away with it. It’s a classic trick in economics and when someone flips between time frames it should immediately raise a red flag for you. But economics isn’t where this concept is most abused. Modern finance has been driven largely by similarly unrealistic models of the world (largely derived from the same general models that Friedman and the Chicago School of Econ devised back in the 50s, 60s and 70s). For instance, take the concept of the Efficient Frontier which generally looks something like this: Basically, stocks will outperform cash and bonds over the long term. But there’s that term again – the “long term.” As Cliff Asness recently showed the “short term” doesn’t add much clarity here because asset prices perform with a high degree of randomness over a 5 year period. But how well does the concept of the “long term” really apply to someone’s life? I want to revisit the Intertemporal Conundrum because I think it’s a crucial concept in portfolio construction that often goes overlooked when applying overly simplistic models like the ones espoused by proponents of Modern Portfolio Theory. Most people begin investing in their 20s, but don’t accumulate a significant chunk of assets until their 30s or 40s. So this gives most of us a time frame of about 25-35 years before retirement. Of course, our financial lives aren’t one clean linear ride from our 20s to retirement. There’s the wedding, the kids, the college tuitions, the new house, the cars, etc. Our financial lives don’t actually reflect a “long term” at all. They’re more like a series of short terms inside of a long term. But it gets more problematic as you apply this. Modern Portfolio Theory will tell you that as you near retirement, you should ratchet back your equity holdings to reduce the volatility in your portfolio because you no longer have a “long term” time horizon. But this is problematic because it means that the 30 year old investor with a 70/30 stock/bond allocation doesn’t really have 70% of their portfolio invested for “the long term.” When they ratchet it back to a 60/40 at age 40 10% of their 70% equity holding will have only been invested for a 10 year time horizon. And when they ratchet back to a 50/50 at age 50 almost a third of their equity portfolio will have been invested for a 20 year period. This all becomes even more problematic because our earnings tend to increase as we get older which means we are contributing more dollars per portfolio size as we age. And when you combine this with the necessary near-term spending needs that often arise as a result of life’s short-term events then our “long term” portfolios suddenly don’t mesh with the MPT story all that well. That is, our “long term” actually proves to be a series of “short terms.” Applying a “long term” to the Efficient Frontier makes it work in theory, but in reality it proves to be far less useful. I advocate treating people’s portfolios like a Savings Portfolios for a very specific reason ( see here for more detail ). I think it’s crucial to treat these portfolios as a place where we create stability and certainty in our necessarily short-term financial lives. The ideas espoused by MPT are not only unrealistic textbook models, but they often lead people to believe that they can afford to take more risk than they should simply because they believe stocks always outperform bonds in the long term. And when you combine all of this with our inherent behavioral biases, you get a situation that is ripe for mistakes. That is, our textbook models trick us into thinking we can handle a lot of risk, but when reality strikes we often realize that the textbook model led us astray. And by then it’s too late. And sadly, the vast majority of Wall Street firms rely on models that are some derivative of this sort of thinking. This doesn’t mean that the concept of the “long term” is useless and it certainly doesn’t mean that short-term market timing is necessarily good. But we have to be very careful about how we go about applying this to our actual financial lives. While the “long term” often sounds great in theory, it often turns out to be a disaster in reality.