Buying Stocks Trading Below Net Current Asset Value Vs. Market Timing

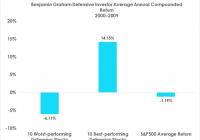

Given the fees derived from selling funds to the retail public, financial institutions have little incentive to be bearish on the stock market. These financial behemoths want euphoric investors believing that Wall Street is Lake Wobegon , where every day is a sunny day and all of the stocks are above average. Following the investment strategy of remaining fully invested in stocks and not attempting to time the market does have merit. An academic paper written by Nobel Laureate William F. Sharpe showed the difficulty associated with market timing [i] . Over the study period of 1934-1972, investors who made the decision at the start of every calendar year to be in either cash or stocks had to bet correctly 83% of the time in order to outperform the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P 500®). That is a difficult hurdle to overcome. Given these poor odds of timing the market with such precision, betting black on the roulette table at a casino in Vegas looks attractive by comparison, with free drinks to boot. Should investors heed the warning of Dr. Sharpe by buying a stock index fund and abandoning any attempt at market timing? Let us take a step back for a moment before going “all in” on stocks. Is there a third way to outperform a broad market average other than choosing cash or an index fund with near-perfect timing accuracy? An alternate investment path to consider is Benjamin Graham’s value investing philosophy for the enterprising investor. Graham showed superior portfolio performance by selecting securities trading below net current asset value (NCAV). The NCAV calculation subtracts all liabilities , including preferred stock, from the current assets (the most liquid assets) on a company’s balance sheet. The NCAV calculation is converted to a per share figure, comparing the value to the company’s share price. If Mr. Market quotes the stock price below the NCAV calculation, it can be considered a buy. The chart below shows the long-term performance of restricting stock purchases to ones trading below NCAV and comparing the results to that of the S&P 500®. (click to enlarge) * Portfolio average return calculations include only stocks trading below 75% of NCAV, with no more than a 5% weighting in any one stock. Dividends and transaction fees are included in all of the calculations. As indicated on the chart, NCAV stocks outperform the index by around six percent on an average annual basis. These stellar results do not require an investor to be permanently in stocks all of the time or to engage in market timing. In approximately three of four years, part of the NCAV portfolio remained on the sidelines sitting in a money market fund. Unlike remaining fully invested in the S&P 500®, investors who restrict their stock purchases to ones trading below NCAV will at times have a portion of capital remaining in cash. These idle time periods out of the stock market due to the lack of NCAV investment opportunities occur in both advancing and declining calendar years. If the stock market moves higher for the calendar year and few stocks trade below NCAV, the portfolio will lag a fully invested index fund. If the stock market has a good year, sitting in cash turns out to be a mistake. As indicated in the chart above, temporary time periods where the NCAV remains idle in cash does not result in long-term underperformance in comparison with the S&P 500® broad market average. Embracing this form of deep value investing has the added benefit of being agnostic regarding the direction of the overall stock market. Market timing is not an issue when it comes to purchasing only stocks trading below NCAV. Investors can ignore what prognosticators on Wall Street think stocks are going to do in the future. The efficient market hypothesis implies that greater portfolio volatility must be accepted in order to achieve a greater average rate of return. There is truth to this argument. Markets are generally efficient, and the NCAV portfolio does fluctuate more than the S&P 500® does. If our measure of risk changes from portfolio volatility to worst-case return, a wrinkle in the market efficiency gospel bubbles up to the surface. We know from behavioral finance research that losses are far more painful to investors than is the satisfaction derived from an equivalent-sized gain. Using a worst-case annual return as our alternate measure of portfolio risk makes sense if money lost is more important to investors than money won in the stock market. As shown in the table below, using the worst annual stock market loss as our measure of portfolio risk, the NCAV portfolio does not suffer through as bad of a drawdown. For many years over our study period, the NCAV portfolio was not fully invested in stocks. When a portion of capital remains on the sidelines for the NCAV portfolio, it makes sense that a worst-case calendar year loss is less severe in comparison with a fully invested stock index fund, such as the S&P 500®. As already shown, this more limited exposure to stocks by investing only in securities trading below NCAV does not result in the average compounded return falling below the S&P 500® over the long term. (click to enlarge) Market timing is an exercise in futility for individual investors. As I pointed out in a previous blog , focusing on individual stock selection using a time-tested value-investing criterion, such as NCAV, is a far more productive use of an investor’s time rather than attempting to figure out the future direction of the overall stock market. Stocks trading at a deep discount to NCAV not only outperform the market over the long term but also benefit from limited downside losses when knee deep in a bad year for stocks. Although not shown in the chart, the second and third worst annual returns of the S&P 500® had a deeper drawdown than the index’s matching year NCAV portfolio return did. A patient investor willing to endure temporary time periods when deep value investing falls out of favor can still do well over the long term. This holds true without the additional requirement of prescient forecasting on the future direction of stocks. [i] Financial Analysts Journal. “Likely Gains from Market Timing” by William F. Sharpe – March/April 1975, Volume 31 Issue 2 pp. 60-69.