Risk Is The Dark Matter Of Portfolio Management

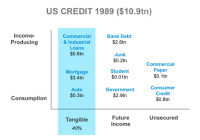

By Ron Rimkus, CFA In 1932, a Dutch astronomer measuring the motion of the stars in the Milky Way noticed something odd in his calculations: The orbital velocities didn’t match up with the visible amount of mass in the galaxy. In response to this observation, he theorized that dark matter – invisible, undetectable matter – must be present in massive quantities to explain the observed movement of heavenly bodies. This is a lot like risk management in the field of investing. Many investors today use a broad array of mathematical tools to track the movements of security prices, sectors, factors, benchmarks, portfolio characteristics, alpha, beta, smart beta… you name it. Yet these tools failed to predict the last crisis in 2008. In fact, historically, they have failed to predict every crisis. And they will fail to predict any crisis in the future. There is much more to risk than the observed movement of security prices. Quite simply, measuring risk is not what such tools do – at least not in any absolute sense. Tools like factor exposures, tracking error, value-at-risk (VaR), growth, value, momentum, and smart beta only measure the relationship of one group of securities relative to another group of securities. But they do serve a purpose. Many investors use them to better understand how their portfolio behaves relative to another portfolio, or to compare relative exposures to interest rates, oil prices, etc., which of course are perfectly valid uses. But they also tell you something about historical relationships that can and frequently do change – often implying that the observed relationship will continue. In statistical parlance, when it comes to the future, these tools are often applied “out of sample.” Typically, these tools work just fine… until they don’t. They’re great when comparing a client’s portfolio with the S&P 500 Index, for example. But what happens if the S&P 500 goes over a cliff? Is it sufficient to say, “Yeah, but our portfolio model went over the cliff with less volatility and a lower tracking error, too!” The real risk, of course, is that clients fail to meet their goals. Don’t get me wrong; these tools have their place. But many investors believe they can adequately measure and describe risk with them. Unfortunately, the tools of risk management are inadequate to describe risk in any absolute sense. What these tools really measure is relative risk, not absolute risk. Consequently, absolute risk is like dark matter. It governs the behavior and performance of securities markets but is not easily measured. So, we often ignore it. But we do so at our own peril. Of course, understanding relative risk can be both interesting and useful. But success is judged against the goals one is trying to achieve. If an investment manager uses these tools to understand his intended and unintended bets against the market, they can be quite helpful. If the manager uses them to create closet index funds, however, then it is simply self-serving. What happens is that the portfolio might closely mirror – or even beat – the performance of the index for many periods, but the two are in essence the same. All too often portfolios using these tools disguise a sad reality: They deliver market-like performance at active management prices. So, where today can we find examples of rising absolute risk that is likely undetected by today’s tools of relative risk? I’m glad you asked. Consider for a moment the broad stretch of financial history. It used to be that currency was backed by gold and loans were backed by tangible assets (e.g., mortgages are typically backed by homes). Both instruments gave their owners legal claims to real assets in the event of default. This approach helps establish trust between two parties in a transaction. During much of the 19th century, the world operated on what is known as the classical gold standard, in which currencies were backed more or less one-for-one with gold. Why did this come about? Why did any country ever have a gold standard? Because people can trust gold – in an absolute sense. Governments can’t print gold. But the world has long since abandoned the classical gold standard, so the fundamental trust and stability conveyed by gold is almost always out of sample in the context of today’s data and mathematical tools. Likewise, back in the 19th century, loans were fully backed by tangible assets. Lenders would let other people borrow only if they had the right to recover money if a borrower defaulted. And government debt typically traded with a risk premium over corporate bonds. By backing loans with collateral, borrowers don’t need income to fulfill their obligations to lenders. Collateral creates trust in the financial system. Over time, however, the use of real assets to back these claims, whether currency or loans, has been whittled away by numerous small changes. Today, currency is no longer backed by anything, and loans are increasingly backed by nothing but the earning power of the borrower. So, the fundamental reason for people to trust currency and credit has slowly shifted from a sound claim on tangible assets to a speculative claim on future income. Now, so long as future income is healthy, there isn’t necessarily a problem. Trust is intact. But what happens when the future income fails to materialize? That’s right: default. So, the transition from relying on tangible assets to future income increases the risk to the entire system. This is systemic risk. Where exactly does this systemic risk show up? Is it in time series data of security prices or spreads from the past 10, 20, or 30 years? No. Is it in your factor exposures relative to the benchmark? How could it be? Is it even showing up in interest rates or spreads? Hardly. Curiously, over the last 25 years, the United States has seen a marked increase in credit without collateral in the form of credit cards, student loans, bank financing, junk bonds, government bonds, etc. With these instruments, borrowers repay by using their future income to meet obligations. By charging high rates of interest, lenders anticipate a percentage of borrowers won’t have adequate future income and will default. Therefore, lenders charge interest rates in excess of the expected default rate to earn a spread (among other things). But this comes with a cost. Borrowers must have income in order to repay. At the macro level, personal income must grow and jobs must be abundant in order to have healthy credit markets. In the absence of a healthy economy, it all comes racing back to trust. And without income or collateral, trust becomes scarce. Consider now the debt profile of the United States over the last 25 years. The first chart shows that about 40% of debt in the United States was backed by tangible assets in 1989. The second graph shows that only about 29% of debt in the United States was backed by tangible assets in 2014. Moreover, collateral requirements in the system have been weakened as loan-to-value (LTV) ratios have risen substantially in mortgages, for instance. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, LTV ratios increased from roughly 83% in 1989 (meaning the average borrower put 17% down and borrowed the rest) to about 93% as of 2010 (the latest date for which these data were published). An LTV of 93% means that the home price need only fall by more than 7% in order for the loan to be underwater and the bank to be at risk of losses of principal (equity). Because LTV ratio data capture home values at date of purchase and do not capture current values of homes (which fluctuate in the market), the picture could be much worse than the data suggest. For instance, in a down market like the one the United States had from 2007-2011, the LTV ratios are much higher and the buffers in the financial system are consequently much lower. And this is for the one-quarter of U.S. debt that is backed by tangible assets. So, what about the rest of the debt? About three-quarters of U.S. debt is now supported solely by future income. This means a massive increase in systemic risk over time. These changes have occurred incrementally over many decades, so much of the increases in systemic risk are out of sample. Few people recognize the totality of the change from beginning to end. Small, incremental changes that add up to big changes over time are typically missed by the market. And this is due, at least in part, to the investment profession relying statistical tools like standard deviation, factor exposures, VaR models, etc. But make no mistake: The safety and soundness of the system has fundamentally changed. How is this possibly reflected in the day-to-day volatility of benchmarks? Or how about the covariance of a portfolio with oil prices over the last 10 years? Ten years is, after all, a small fraction of the time it took for today’s financial system to evolve. We now have an economy and money supply that grows with credit expansion. But credit is expanding rapidly while economic growth is faltering. A premise of modern central banking is that lower interest rates drive credit growth, which in turn drives economic growth. But what happens if credit expansion reaches a tipping point and lower rates fail to grow the economy? Isn’t that risk? Are we there now? Over the last 100-plus years, the United States has shifted the security of its currency and credit from fully backed collateral to promises based on the future income of borrowers. And in doing so, it has largely abandoned the idea that obligations can be made whole with tangible assets. At the very bottom of it all, the reason to trust U.S. currency and credit has declined. So, the risk in the system has markedly increased, but where is that risk captured and calculated? How exactly does that manifest itself in market prices? What about a portfolio manager whose strategy is based on investing in illiquid assets in a liquid world? What happens if liquidity changes should stop economic growth? Perhaps when the economy stops growing, we will all find out how much absolute risk has grown over the years regardless of what your relative risk tools are telling you. In the end there is but one question to consider: Is there some dark, mysterious force holding the financial universe together? Or will it all come flying apart?