5 Ways To Beat The Market: Part-3 Revisited

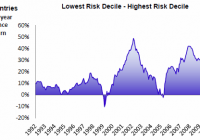

In a series of articles in December 2014, I highlighted five buy-and-hold strategies that have historically outperformed the S&P 500 (SPY). Stock ownership by U.S. households is low and falling even as the barriers to entering the market have been greatly reduced. Investors should understand simple and easy to implement strategies that have been shown to outperform the market over long time intervals. The third of five strategies I will revisit in this series of articles is the “low volatility anomaly” which has seen lower volatility stocks produce higher risk-adjusted returns over time. In a series of articles in December 2014, I demonstrated five buy-and-hold strategies – size, value, low volatility, dividend growth, and equal weighting, that have historically outperformed the S&P 500 (NYSEARCA: SPY ). I covered an update to the size factor published on Wednesday , and posted an update to the value factor on Thursday. In that series, I demonstrated that while technological barriers and costs to market access have been falling, the number of households that own stocks in non-retirement accounts has been falling as well. Less that 14% of U.S. households directly own stocks, which is less than half of the amount of households that own dogs or cats , and less than half of the proportion of households that own guns . The percentage of households that directly own stocks is even less than the percentage of households that have Netflix or Hulu . The strategies I discussed in this series are low cost ways of getting broadly diversified domestic equity exposure with factor tilts that have generated long-run structural alpha. I want to keep these investor topics in front of the Seeking Alpha readership, so I will re-visit these principles with a discussion of the first half returns of these strategies in a series of five articles over the next five days. Reprisals of these articles will allow me to continually update the long-run returns of these strategies for the readership. Without further ado, one of my favorite and most oft discussed strategies on Seeking Alpha… Low Volatility Since the groundwork behind the Modern Portfolio Theory was laid fifty years ago, it has been axiomatic that riskier portfolios should expect to be compensated with higher returns. More recent academic research has shown that this assumption holds less well at the extremes – the least risky stocks tend to outperform the most risky stocks on both a risk-adjusted and an absolute basis. In a 2012 paper by Nardin L. Baker of Guggenheim Investments and Robert A. Haugen of Haugen Custom Financial Systems entitled: ” Low Risk Stocks Outperform Within All Observable Markets of the World “, the pair demonstrated that in their thirty-three country sample the highest risk decile of stocks, rebalanced monthly, underperformed the lowest risk decile of stocks in each locale. Source: Nardin & Baker (2012) In 2013, Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Pedersen, each affiliated with hedge fund AQR Capital Management, published ” Buffett’s Alpha “, which deconstructed the return profile of Berkshire Hathaway ( BRK.A , BRK.B ). In “Buffett’s Alpha”, the authors determined that the public stocks owned by Buffett in 13F filings had only a market beta of 0.77 from 1980-2011. Over that thirty-one year period, Buffett outperformed the market while owning in the public portion of his portfolio securities which on average had only three-quarters of the market beta. At the 1999 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting, Buffett, during the rising crescendo of the tech bubble stated: “We’re more comfortable in that kind of (traditional) business. It means we miss a lot of very big winners. But we wouldn’t know how to pick them out anyway. It also means we have very few big losers – and that’s quite helpful over time. We’re perfectly willing to trade away a big payoff for a certain payoff.” From the chart above by Haugen and Baker, the end of the 1990s was the period when the most volatile stocks were actually outperforming the least volatile stocks as earnings multiples for start-ups in the tech space reached stratospheric heights. Buffett, as his 1999 quote illustrates, chose to pass and his relative performance in the short-run faltered, but over the long run he avoided the tech bubble-fueled market meltdown. Missing these major market corrections has been a predominant source of Buffett’s sustainable alpha. This is consistent with the return profile for the low volatility strategy as seen in the cumulative graph of the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index versus the S&P 500 below. Low volatility stocks underperformed during the run-up to the tech bubble, but strongly outperformed in the aftermath and through the financial crisis. (click to enlarge) Source: Standard and Poor’s; Bloomberg Buffett has historically been called a “value investor”, but as we saw in my second article in this series, while value investing produces higher long-run returns, it also has higher variability of returns. The AQR researchers saw low volatility investing and leverage as key to Buffett’s success, and I have chosen to discuss them in this series as separate, but related strategies. From an analytic standpoint, the correlation coefficient of the S&P Pure Value Index and the S&P Low Volatility Index has been roughly equivalent to the correlation between the S&P 600 Smallcap Index ( covered in my first article in this series ) and low volatility stocks, and few would argue that the latter pair has exposure to similar risk factors. Certainly, Buffett’s ability to miss the bursting of the tech bubble was highly correlated with the return series for low volatility stocks above. If we can take a subset of the broader market, low volatility stocks, and demonstrate that they have outperformed, then another segment of the market must be underperforming. Over the twenty-year plus time period we are examining, high beta stocks have fit that mold, and that underperformance is captured in the graph of the cumulative returns of low volatility stocks and high beta stocks below: (click to enlarge) Source: Standard and Poor’s; Bloomberg Two of the three authors of “Buffett’s Alpha”, Andrea Frazzini and Lasse Heje Pederson also collaborated on ” Betting Against Beta ” where the researchers demonstrate that since leverage constrained investors bid up high-beta assets, that high beta is necessarily associated with lower alpha. The articles demonstrates the underperformance of high beta across more than 20 global equity markets and several fixed income markets. This analysis makes intuitive sense. Long-only active managers who are benchmarked against an index naturally seek higher beta assets as a means to outperformance, but the cumulative effect of this preference for riskier assets lowers their expected forward returns as compared to disfavored lower beta stocks. Behavioral explanations including lottery preferences, representativeness, and overconfidence have also been suggested for the relative underperformance of high volatility stocks. The S&P 500 Low Volatility Index is replicated through the exchange traded fund, Powershares S&P 500 Low Volatility Portfolio (NYSEARCA: SPLV ), which carries a 0.25% expense ratio. The raw beta of this fund over the trailing 1-year is just 0.84, which compares reasonably to the historical beta that Buffett had realized in the aforementioned study. My favorite part of this low volatility strategy for buy-and-hold investors with a long-term horizon is that the strategy has outperformed when the stock market has been falling, besting the broader market in 2000-2002 and 2008. The low volatility strategy underperformed the most in 1998 and 1999 as tech multiples ballooned and Buffett was forced to defend his underperformance, but the strategy far outpaced the broader market in the 2000-2002 correction. While low volatility stocks have historically outperformed the broader market, they lagged in the first half of 2015. Part of this underperformance mirrors the weak relative performance by low volatility stocks during the rate-related selloff in 1994 (see first half returns below). As the rate selloff in 2015 has reversed in the very early days of the second half of the year, low volatility stocks have outperformed the broader market by nearly 2%, quickly erasing over half of their year-to-date deficit. While the Low Volatility Index will be more sensitive to higher interest rates than other segments of the equity market, I continue to expect that low volatility stocks will continue to offer attractive risk-adjusted returns over the business cycle. As I wrote in my 10 Themes Shaping Markets in the Back Half of 2015 , stretched equity multiples domestically will necessitate that valuations be driven by changes in earnings, tempering further price gains. As equity prices rise, investors may look to opportunistically rotate into underperforming rate-sensitive assets and lower volatility assets. Given the tendency for lower volatility assets to outperform in falling markets, investors may desire to rotate to lower volatility stocks which have underperformed in 2015. I will be publishing updated results for two additional proven buy-and-hold strategies that can be replicated through low cost indices over the next couple of days. Disclaimer My articles may contain statements and projections that are forward-looking in nature, and therefore inherently subject to numerous risks, uncertainties and assumptions. While my articles focus on generating long-term risk-adjusted returns, investment decisions necessarily involve the risk of loss of principal. Individual investor circumstances vary significantly, and information gleaned from my articles should be applied to your own unique investment situation, objectives, risk tolerance, and investment horizon. Disclosure: I am/we are long SPY, SPLV. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.