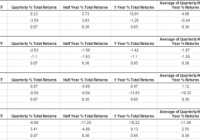

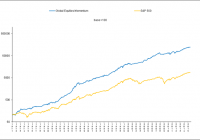

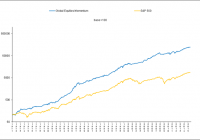

When doing financial modeling, one of the first things to look at is if your empirical work makes sense. In other words, are there valid economic reasons why a model should work? This can help you avoid drawing erroneous conclusions based on creative data mining. [1] Next, you should look for robustness. This can take several forms. One of the most common robustness tests is to see how well a model does when it is applied to somewhat different markets. Even though equities have historically offered the highest risk premium, it is desirable to see a model do well when it is also applied to other financial markets. Another robustness test is to see if a model is consistent over time. You do not want to see success based on spurious short periods of good fortune. Similarly, you would like to see a model hold up well over a range of parameter values. Getting lucky can be good in some things, but not in financial research. Relative and absolute momentum have held up well according to all of the above criteria. But now that momentum is attracting more attention, it is important to remain vigilant and to keep robustness in mind. What makes this especially true is the natural tendency to come up with modifications and “enhancements” that can add complexity to a once-simple model. An interesting new paper by Dietvorst, Simmons, and Massey (2015) called ” Overcoming Algorithm Aversion: People Will Use Algorithms if They Can (Even Slightly) Modify Them ,” shows that people are considerably more likely to adopt a model if they can modify it. Everyone likes to feel that they have some personal involvement with a model, and that they may have made it better. But simpler is often better in the long run. Data-mined “enhancements” may fit the existing data well, but may not hold up on new data or over longer periods of time. I have seen dozens of variations and “enhancements” to momentum, and I will undoubtedly see many more in the days ahead. One variation that attracted considerable attention a few years ago was by Novy-Marx (2012), who found that the first six months of the lookback period for individual stocks gave higher profits than the more recent six months. This became known as the “echo effect.” However, it never made much sense to me. So I tested the echo effect on stock indices, stock sectors, and assets other than stocks. I was not surprised when incorporating the echo effect gave worse results than the normal way of calculating momentum. A subsequent study by Goyal and Wahal (2013) showed that the echo effect was invalid in 37 markets outside the U.S. Goyal and Wahal also demonstrated that the echo effect was largely driven by short-term reversals stemming from the second to the last month. Overreaction to news leading to short-term mean reversion of individual stocks does make sense. Prior to that time, only the last month was routinely skipped when calculating momentum for stocks. [2] Based on this finding, the latest research papers skip the prior two months instead of just the last month when calculating individual stock momentum. [3] While robustness tests are very important, the best validation of a trading model is to see how it performs on additional out-of-sample data. The statistician W. Edwards Deming once said, “In God we trust; everyone else bring data.” When I first developed the dual momentum-based Global Equities Momentum (GEM) model, my backtest went to January 1974. This is because the Barclays Capital bond index data I was using began in January 1973. I am now able to access Ibbotson bond index data, which has a much longer history. My GEM constraint has now changed to the MSCI stock index data going back to January 1970. Having this additional bond data, I have another three years of out-of-sample performance for GEM. My new backtest includes the 1973-74 bear market, and shows dual momentum sidestepping the carnage of another severe bear market. (click to enlarge) GEM is more attractive than it was previously on both an absolute basis and relative to common benchmarks. Here is summary performance information from January 1971 through July 2015. 60/40 is 60% S&P 500 and 40% Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Bonds (prior to January 1976, Ibbotson U.S. Government Intermediate Bonds). Monthly returns (updated each month) can be found on the Performance page of our website. GEM S&P 500 60/40 Ann Rtn 18.2 11.9 10.2 Std Dev 12.5 15.2 9.8 Sharpe 0.91 0.38 0.44 Max DD -17.8 -50.9 -32.5 Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our GEM Performance and Disclaimer pages for more information. In our next article, we will look at longer out-of-sample performance using the world’s longest backtests. Fortunately for us, these were done to further validate simple relative and absolute momentum. [1] For example, between 1978 and 2008, U.S. stocks had an annual return of 13.9% when a U.S. model was on the cover of the annual Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue versus 7.2% when a non-U.S. model was on the cover. [2] Short-term mean reversion is not an issue with stock indices or other asset classes, so the last two months do not need to be excluded from their momentum lookback period. [3] See Geczy and Samonov (2015). The discovery of two-month mean reversion is an example of the Fleming effect in which different but related research can lead to serendipitous results.