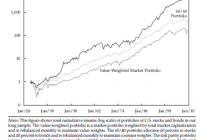

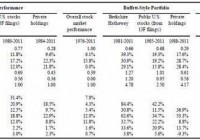

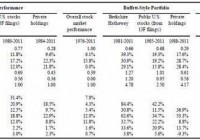

Summary This series offers an expansive look at the Low Volatility Anomaly, or why lower risk stocks have historically produced stronger risk-adjusted returns than higher risk stocks or the broader market. This article offers empirical evidence that one of the most successful investment minds of a generation has capitalized on this anomaly. By adding financial leverage to lower risk businesses, Berkshire Hathaway has generated higher risk-adjusted returns historically. Given the long-run structural alpha generated by low volatility strategies, I wanted to dedicate a more detailed discussion of the efficacy of this style of investing for Seeking Alpha readers. In recent articles, I have provided readers a detailed theoretical underpinning of the strategy. In this article and subsequent pieces, I am going to provide empirical evidence across markets that depicts the success of a low volatility bent. Empirical Evidence of the Low Volatility Anomaly Since the evolution of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) in the early 1960s, it has been axiomatic in modern finance that expected returns are a function of an asset’s systematic risk, or beta, when the asset is added to a well-diversified portfolio. As discussed throughout this series thus far, the simplifying assumptions underlying CAPM provide frictions between model and market. These conventions underlying CAPM include that markets are wholly efficient, investors can lend and borrow unlimited amounts at the risk-free rate, trade fee of transaction costs and tax implications, and that the variance of returns is an adequate measure of risk in a world where asset returns are not normally distributed. Despite these shortcomings, the general CAPM framework has largely become broadly embedded in capital budgeting and, in part, market expectations. The presentation of empirical evidence on the Low Volatility Anomaly is greatly strengthened when you can demonstrate its role in the success of one of the greatest investors of our time. In 2013, Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Pedersen, each affiliated with hedge fund AQR Capital Management, published ” Buffett’s Alpha “, which deconstructed the return profile of Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A ) (NYSE: BRK.B ). From their analysis, the authors found: “the general tendency of high-quality, safe, and cheap stocks to outperform can explain much of Buffett’s performance and controlling for these factors makes Buffett’s alpha statistically insignificant.” That is a powerful statement. In a set-up to their attention-grabbing assertion, the authors demonstrated that of all stocks that traded for more than 30 years between 1926 and 2011, Berkshire Hathaway had the highest Sharpe Ratio. Buffett also magnified these risk-adjusted excess returns through the deployment of leverage estimated by the authors to be at a level of 1.6 to 1 on average. The leverage came both in the form of borrowings, which benefited from Berkshire Hathaway’s very high quality credit rating, and through float from his insurance subsidiaries. To demonstrate that Buffet’s tremendous performance was a function of this tendency to buy low risk stocks and employ conservative levels of investment leverage, the authors created tracking portfolios to mimic Buffett’s market exposure and active stock-selection themes, leveraged to the same active risk as Berkshire Hathaway. (click to enlarge) The Buffett-tracking portfolio performs comparably to the best-in-class performance of Berkshire Hathaway, demonstrating that Buffett is less a sage stock picker than a principled practitioner who has long understood the Low Volatility Anomaly and who had an investment vehicle that allowed him to avoid costly liquidations in times of stress. Note that Buffett’s average beta of his public stock holdings was just 0.77. In addition to the impressive long-run alpha demonstrated by Buffett’s leveraging of low volatility assets, another glaring failure of CAPM can be seen in the returns of the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index and the S&P 500 High Beta Index. These two indices form portfolios of the one hundred highest and lowest volatility stocks in the S&P 500 Index based on the standard deviation of price changes of the trailing 252 trading days. The indices are then rebalanced quarterly. The performance of these strategies was backtested to 1990, and demonstrates that returns would have been directionally opposite of what would be predicted by CAPM with low volatility stocks (replicated by the PowerShares S&P 500 Low Volatility Portfolio ETF (NYSEARCA: SPLV )) strongly outperforming high beta stocks (replicated by the PowerShares S&P 500 High Beta Portfolio ETF (NYSEARCA: SPHB )). (click to enlarge) Source: Standard and Poor’s; Bloomberg Joining these two examples, Buffett’s recent notable purchases have conformed to the idea of levering low volatility equities. When Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital combined to purchase H.J. Heinz in February 2013 , Heinz was the fifteenth largest constituent in the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index, putting the company in the 97th percentile of the S&P 500 in terms of trailing realized volatility. Buffett’s initial investment included an $8B preferred stake with a high fixed coupon, further dampening the volatility of the cash flow returns his enterprise received as part of the deal. The Berkshire/3G Capital combination would further expand their bet on the low beta packaged food sector in March 2015 with the purchase of a controlling stake in Kraft Foods Group (NASDAQ: KHC ). When Berkshire Hathaway’s Mid-American Energy unit purchased NV Energy in June of 2013 , the stock had a trailing twelve month beta of 0.73 and electric utilities were the largest individual sector weighting of the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index. When Berkshire’s utility unit had made an early purchase of Pacificorp in 2006, it was reported in Electric Utility Week that Buffett told Oregon regulators that owning utilities was “not a way to get rich – it’s a way to stay rich.” This quote came in the two years following Texas Pacific’s failed bid for Oregon’s Portland General Electric (NYSE: POR ) and KKR’s nixed acquisition of Arizona’s Unisource ( OTCPK:USRC ). Regulators at the time were concerned that these private equity firms would purchase the utility holding companies with excessive financing, the cost of which could be explicitly borne by customers in the form of higher rates and implicitly through backlogged maintenance, as capital expenditures were crowded out by debt service payments. With the notable exception of the disastrous TXU leveraged buyout in 2007, the industry has largely eschewed large scale leveraging transactions in favor of incremental releveraging through conservatively financed share repurchase plans and above market dividend rates. With regulated returns on equity, utilities generate stable and predictable cash flows for strong operators, making Buffett’s desire to lever the cash flow streams of these companies highly consistent with his long established track record of buying stable businesses. Warren Buffett’s tremendous long-run performance is in large part attributable to his early understanding of the relative outperformance of lower risk and stable businesses. In my next article in this series, I will demonstrate a way to capitalize on the Low Volatility Anomaly in the fixed income market. Disclaimer My articles may contain statements and projections that are forward-looking in nature, and therefore inherently subject to numerous risks, uncertainties and assumptions. While my articles focus on generating long-term risk-adjusted returns, investment decisions necessarily involve the risk of loss of principal. Individual investor circumstances vary significantly, and information gleaned from my articles should be applied to your own unique investment situation, objectives, risk tolerance, and investment horizon. Disclosure: I am/we are long SPLV. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.